History – the Brothertown Indian Nation

The Brothertown Indian Nation History By Craig Cipolla and Caroline Andler

For a companion resource, see the extensive Brothertown Time Line (written by Caroline Andler and Courtesy of the Brothertown Citizen)

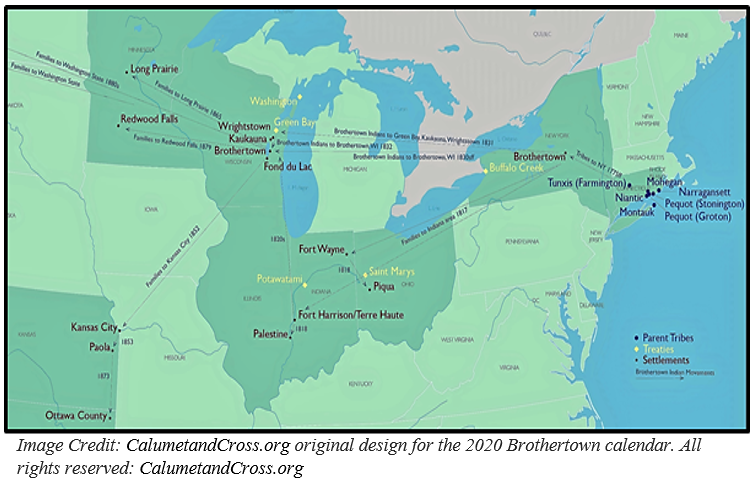

The story of the Brothertown Indian Nation spans only 230 years at most but covers a distance of more than 1,000 miles from the East Coast to upstate New York and finally to Wisconsin. This is not to say that Brothertown histories are detached from deeper Indigenous histories that reach back to early colonial- and pre-colonial times; the community of Brothertown is made up of the descendants of Mohegan, Eastern Pequot, Mashantucket Pequot, Niantic, Narragansett, Montauk, and Tunxis peoples that had come to practice Christianity in the 18th century and were tired of their living conditions on the East Coast where resources were few and colonial usurpers plentiful.

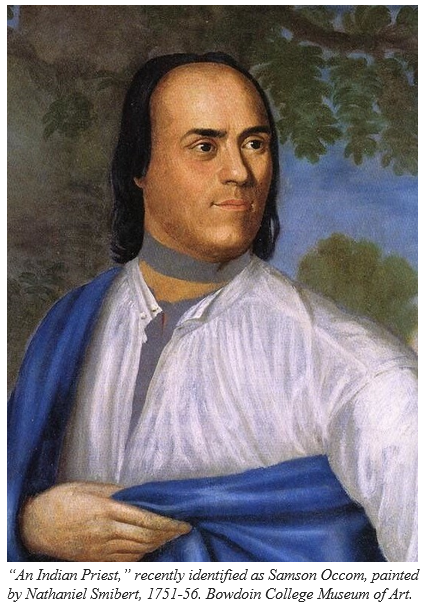

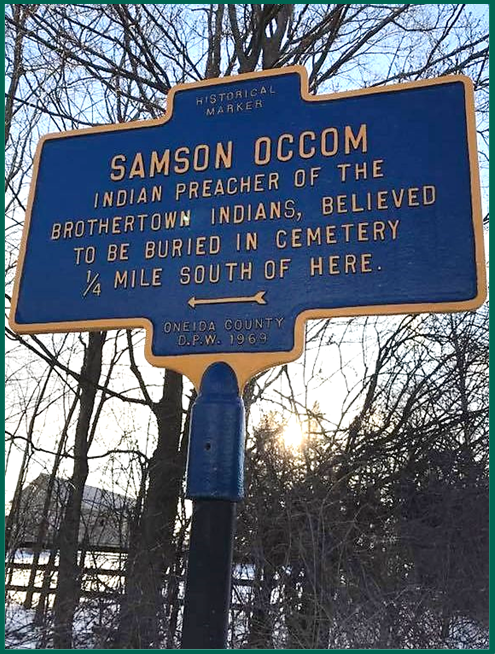

A central influence behind the Brothertown movement was Samson Occom. He was born at Mohegan in 1723 (Love 1899: 21-22; Murray 1998). Occom became Christian and dedicated his life to spreading Christianity to indigenous people in his late teens. At age 20, Occom went to live and study with Eleazor Wheelock, a Euroamerican missionary, at the Indian Charter School. Occom studied for just over 4 years and then went out to spread the Christian message. He lived and worked among the Montauk people at first and then went to set up a mission in Oneida country in New York. There he forged strong ties that would later prove to be important for establishing the first Brothertown settlement in New York. In the mid-1760s, Occom moved back to Mohegan territory in Connecticut, where he built a house and a church to continue preaching in his home community.

In the late 1760s, Occom agreed to go to England to raise funds for missionary efforts in New England; he was backed by many of New England’s religious officials, including his mentor Eleazor Wheelock. In England, Occom raised considerable funds to spread Christianity to New England’s Native peoples. Upon his return, however, Wheelock diverted the funds and used them for purposes Occom did not agree with. Wheelock started a school in New Hampshire (Dartmouth College) with the funds that Occom raised. Occom opposed this idea on the grounds that the locale was not proximal enough to the indigenous communities that he saw as needing the most help. In addition to this, Wheelock began training only Euroamerican students as he thought it was the most efficient means of spreading Christianity to indigenous communities.

These tensions led Occom to critically reevaluate indigenous peoples’ places in coastal New England. He came to think that there was nothing left for Indians in New England except for misery and vice (Love 1899: 169-176). Because of this, he began contemplating an emigration that would separate indigenous peoples from the corrupting influences of Euroamerican lifeways, and allot indigenous peoples more land to cultivate (Love 1899: 208). Joseph Johnson, a young Mohegan preacher and schoolteacher, played a crucial role in planning the move; he came to constitute a driving force behind the Brothertown movement. There were many Christian Indians in New England who would follow Occom and Johnson on their quest. As part of the Great Awakening, Christian sects appeared in many of the tribal communities of the East Coast after the first quarter of the 18th century (Love 1899: 189). The seven communities that would eventually contribute to the Brothertown Nation were the Misquamicut settlement of Charleston, Rhode Island (made up of mostly Narragansett and Niantic peoples), the Mashantucket Pequots, the Eastern Pequots, the Niantics, the Tunxis peoples of Farmington, the Montauck peoples of Long Island, and the Mohegan (Love 1899: 188-204).

In addition to the above reasons for relocation, Occom thought it would be extremely beneficial for the Oneida people if he were to establish an exemplary Christian Indian community that would spread the Christian faith and introduce agriculture in their area (Love 1899: 208). He envisioned the new community as governed in a manner that combined tribal and democratic systems of government. This way, all members would be brothers—hence the name Brothertown. The planning of this new community officially began with a meeting at Mohegan in 1773. The Oneida and the Brothertown set up a formal treaty concerning the land in the same year. The tract was located 14 miles south of Utica in modern-day Paris, New York. As soon as 1774, the Christian Indians of New England began to move out west to their new lands.

Brothertown was officially founded on November 7, 1785. “We now proceeded to form into a Body Politick -We named our town by the name of Brotherton, in Indian—Eeyamquittoowauconnuck” (Occom 1785). Unfortunately, the Brothertown Indians did not escape some of the land issues they had moved west to avoid. Euro-American land speculators and settlers placed constant pressure on them to sell or lease their new lands (Love 1899). In an effort to protect the Brothertown Indians from losing their lands, the New York state government appointed commissioners to advise the tribe and passed laws that forbade the sale/lease of Brothertown lands to Euroamerican settlers (Love 1899). Due to these land conflicts, New York officials divided the Brothertown lands, allowing Brothertown peoples to remain on one part with the other portion to be sold to Euroamerican settlers.

“[T]he said Tract was found to contain as quantity of twenty-four thousand and fifty acres, and the said commissioners thereupon set off a part of the said Tract in one entire piece, containing as appears by the map …nine thousand three hundred and ninety acres for the use of the Indians then residing in Brothertown, and for such other Indians as may be entitled to same in Brothertown, and made a division of the remainder of the land in Brothertown amongst such Lesees and claimants there of as mentioned in the said Act, and sold and conveyed the same to them.”

The funds from these sales went into the Treasury of the State of New York for the benefit of the Brothertown Indians and would later aid them in their move to Wisconsin (Commuck 1855: 294). In the early 19th century, the New York land issues continued as the state government began purchasing large tracts of land from the Oneida territories, which included Brothertown. At this time, Eleazar Williams began talking to the New York Indians about his vision of an Indian Empire in the Michigan territory. This influence, coupled with the land disputes, contributed to the New York Indians’ decisions to look westward for new territories.

In 1821, the New York tribes (Six Iroquois Tribes, Brothertown, Munsee, Stockbridge) worked out a treaty with the Menominee for 860,000 acres of land in Wisconsin. The following year, they added another treaty for 6.72 million acres of additional land. Later, the Menominee refused to honor the treaties. After much dispute, the federal government interjected to settle the conflict with a series of three treaties; the New York tribes received their lands in Wisconsin, although much less than originally agreed upon. A treaty from the late 1830s summarizes these land issues:

“…purchases were made by the New York Indians from the Menomonie and Winnebago Indians of certain lands at Green Bay in the Territory of Wisconsin, which after much difficulty and contention with those Indians concerning the extent of that purchase, the whole subject was finally settled by a treaty between the United States and the Menomonie Indians, concluded in February, 1831, to which the New York Indians gave their assent on the seventeenth day of October 1832: And whereas, by the provisions of that treaty, five hundred thousand acres of land are secured to the New York Indians…”

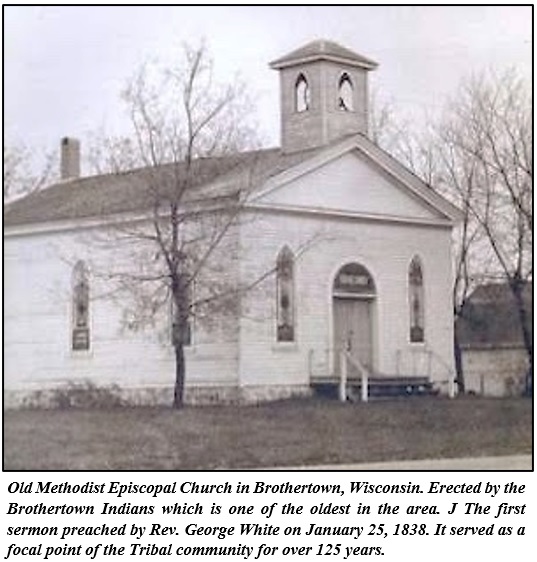

The new land was just east of Lake Winnebago. The Brothertown began emigrating from New York in 1831, staying briefly in Kaukauna. They finally reached the new Brothertown lands in 1832-1833. They cleared and developed the landscape, which was thickly wooded prior to their arrival (Titus 1938). The first houses were located along Mill Creek—the center of the archaeological survey area. In the same area, they built a gristmill: the first mill erected on Lake Winnebago and the second mill made in the entire Fox River Valley. Farmers from all around the area used the Brothertown Mill. It was sometimes so busy that farmers would have to wait 2-3 days for their grains to be processed by the mill. The Brothertown also built a sawmill along the creek. A communal building that served as a church, a meetinghouse, and a school was built in the early 1830s; it sat near Union Cemetery on what is now Lakeshore Drive. Later, in 1842, the Brothertown built a separate church. It was the first Methodist Church built in Wisconsin, and it stood on the corner of present-day HWY 151 and County Road H. The structure was razed in 1967.

The tribe was hardly settled in its new location, having been pressured out of New York and pushed off its land at Kaukauna when a new threat appeared. The federal government entered into negotiations with the tribes in New York and Wisconsin to exchange their land in Wisconsin for land in Indian Territory (Love 1899:321). On January 15, 1838, the United States concluded a treaty at Buffalo Creek, New York (Love 1899:321). Here is an excerpt on the attempted removal of the New York Indians to the territory of Kansas:

“In consideration of the above cessation and relinquishment, on the part of the tribes of New York Indians, and in order to manifest the deep interest of the United States in the future peace and prosperity of the New York Indians, the United States agree to set apart the following tract of country, situated directly west of the State of Missouri, as a permanent home for all the New York Indians, now residing in the State of New York, or in Wisconsin, or elsewhere in the United States….”

The 1838 Treaty of Buffalo Creek, designed to dispossess the six Iroquois tribes and the Brothertown, Stockbridge, and Munsee of their land and remove them to Kansas Territory, put the tribe in jeopardy once again. For much of its history, the Brothertown Indian’s ancestors had found themselves displaced and forced to move. For fifty years in New York, the tribe found its land reduced by an influx of other Indians, then by unauthorized settlement, and then by state action. This pernicious land grabbing had left the Brothertown without enough tillable land to support its members, occasioning the tribe’s movement. The Brothertown Indians then moved to Wisconsin and settled on the Fox River, only to move again to the east side of Lake Winnebago. Then, with the tribe having hardly established its community in Wisconsin, it appeared that it would be pressured to move to Indian Territory in Kansas. The tribe’s one, and possibly only, protection against this was to secure land in the same manner that the lands of the neighboring tribes were secured—by patents in fee simple. By a perversity of law, as long as the land was held in trust by the federal government, common and inalienable, it was subject to loss by government action. It was natural to assume that the best means to protect it was in the same manner as the property of non-Indians—through private ownership. In an effort to remain on the new lands in Wisconsin, the Brothertown headmen requested a Congressional Act that would divide the lands into individually owned plots and grant Brothertown tribal members United States citizenship (Love 1899: 327). They were officially granted citizenship in 1839. The Brothertown subsequently elected a committee of headmen to divide the Wisconsin lands into individual plots.

The language of the Congressional Act may be interpreted by some to indicate that the Brothertown Indians relinquished their tribal status through this request for citizenship and individual title to land. Congress may have intended to act unilaterally to usurp the power of the Brothertown Indians to self-govern through the Act (Loew 2001: 119); however, the Brothertown Indians sought the protection of their land and to prevent yet another forced removal by the federal government. The Brothertown Indians did not seek relief of the right to self govern or to be dissolved as an Indian Tribe. What this language proposed to do was assure that in the governance of the town, territorial and later state law would be in force and not tribal law. In other respects, the power of the tribe to act was not diminished by the statute. The final line in the Act made it clear that the government of the Brothertown Indians could continue other tribal activities, including the collection of annuities.

Provided, however, That nothing in this act shall be so construed as to deprive them of the right to any annuity now due them from the State of New York or the United States, but they shall be entitled to receive any such annuity in the same manner as though this act had not been passed.

The desire of Brothertown Indians to seek such protections must be understood against the backdrop of Indian tribes being removed to lands in the west, as well as the Brothertown’s long history of displacement. The purpose of the 1839 legislation was not significantly different from the General Allotment Act passed nearly fifty years later.

Allotment took its inevitable toll, and the Brothertown quickly lost their lands to foreclosures and tax sales. By 1880, many were living with friends and relatives on the Oneida and Mohican Reservations and, if they were lucky, providing day labor in neighboring white communities. Yet, despite their uncertain political status, the Brothertown continued to function as a tribe. They petitioned Congress over land issues and joined a lawsuit with other New York tribes over treaty matters. In 1878, Congress acknowledged the existence of the Brothertown by inviting the tribe to appoint five trustees to oversee the sale of unallotted tribal land. (Loew 2001:120)

Today, the Brothertown Indians live all across the Midwest and beyond. They have approximately 4,000 members on their rolls and a tribal council office in Fond du Lac. As is evident from this brief history, the Brothertown Indians played a key role in shaping and developing the area of Wisconsin in which they settled in the second quarter of the 19th century. Brothertown history is indeed complex; the Brothertown Indians negotiated colonialism in an incredibly unique and interesting manner, appropriating certain things and practices introduced with colonialism and intertwining them with tribal traditions in order to persevere and maintain their identities as indigenous peoples.

For an expanded timeline of the Brothertown Indian Nation, Click here… (by Caroline Andler and courtesy of BrothertownCitizen.com). The timeline is about 50 pages and is very complete.

References Cited:

Nation Archives, Washington DC 1796 An Act Relative to Lands in Brothertown: Report of the Commissioners to the Legislation of the State of New York. Housed at Hamilton College, New York.

1838 Treaty with the New York Indians, 1838 Report No. 244, February 6, 1839, Petition requesting that the Brothertown Indians be granted U.S. citizenship

Commuck, Thomas 1855 Sketch of the Brothertown Indians. In Wisconsin Historical Collections, Vol. IV.

Loew, Patty 2001 Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Wisconsin Historical Society Press, Madison.

Love, W. DeLoss The Christian Indians of New England. The Pilgrim Press, Boston.

Murray, Laura J., editor 1998 To Do Good to My Indian Brethren: The Writings of Joseph Johnson, 1751-1776. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

Will Ottery and Rudi Ottery 1989 A Man Called Sampson, 1580-1989. Penobscot Press, Weare.

Titus, W.A. 1938 Brothertown: A Wisconsin Story With a New England Background. Quarterly of the Wisconsin Historical Society 21.